Architecture is the silent witness to human innovation and creativity. From the soaring heights of the Burj Khalifa to the understated brilliance of local community centers, every architectural marvel starts as a fragile idea in a designer’s mind. This post dissects the intricate process of taking a mere concept and weaving it into the concrete, steel, and glass structures that grace our cities and landscapes.

Conceiving the Vision: Ideation and Inspiration

The birth of an architectural project is, first and foremost, the birth of an idea. It might spark from an unmet need in a community, a social or environmental issue, or a simple desire to create beauty. In this stage, architects immerse themselves in research, drawing from historical, cultural, and technological reservoirs of knowledge.

Historical Context and Ideation

Architects often begin with historical contexts, examining the evolution of building typologies and styles. How have ancient structures withstood the test of time, and what can contemporary designs learn from them? What societal shifts influenced architectural choices in different periods? By answering these questions, the groundwork for a new design language begins to form.

Cultural and Social Influences

Contemporary architecture must engage with the present and anticipate the future while remaining contextual. By understanding the nuances of culture and society, architects can ensure that their designs resonate with the local community. Are there specific cultural symbols or practices that a building can honor or evolve? Can the architecture address social issues like inclusivity and equitable access?

Technological Advancements and Design Opportunities

Technology is a potent force in the evolution of architecture. From the development of new materials to digital tools that enable complex geometry, each advancement opens doors to new design possibilities. Architects who are mindful of these opportunities can create structures that are not just visually striking but also functional, efficient, and sustainable.

The Blueprint: Design Development

Once the vision is clear, it’s time to put it on paper—or these days, into pixels. The design development phase transforms the abstract idea into a detailed plan. Key stakeholders and the design team collaborate closely to refine the concept and address practical considerations.

Collaborative Workshops and Client Input

Client input is crucial in the design development stage. Architects might host workshops where clients, potential users, and design professionals gather to discuss needs, preferences, and project goals. Through dialogue and iteration, a shared vision emerges, one that balances creative ambition with budgetary and regulatory constraints.

Spatial Planning and Functionality

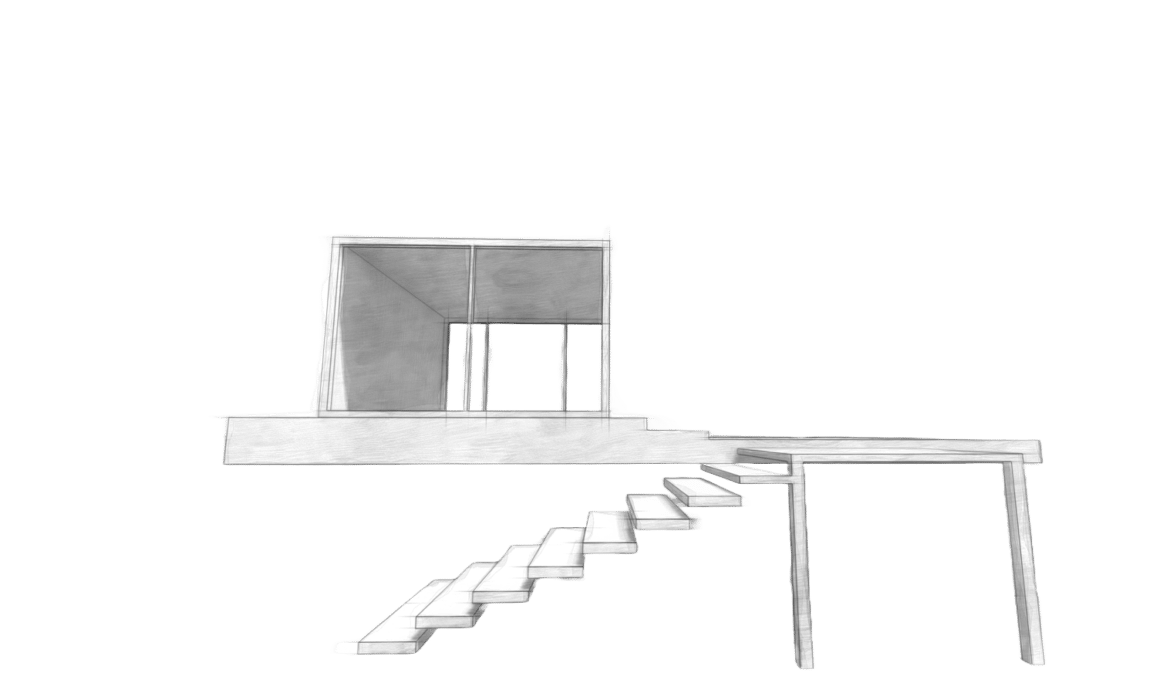

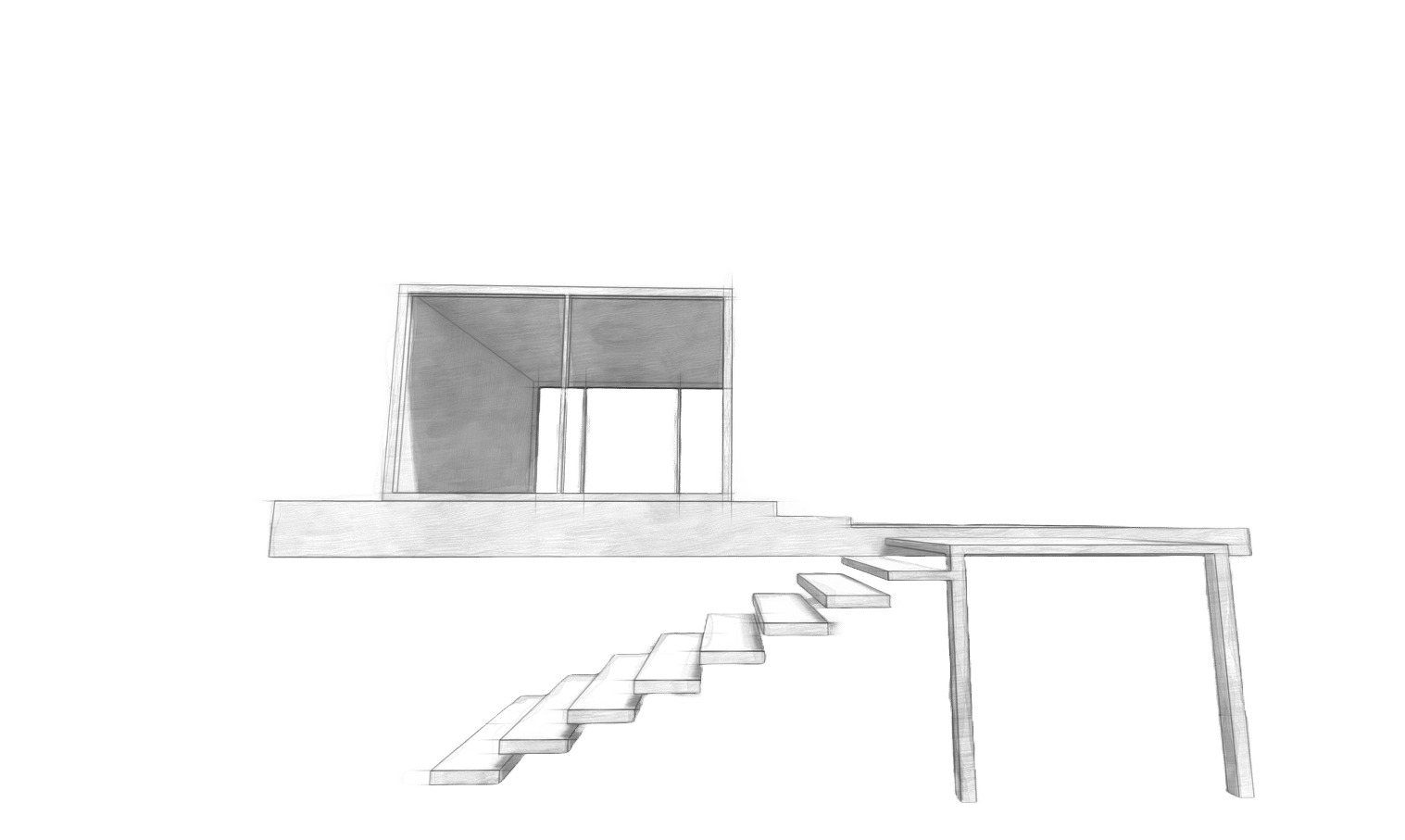

The heart of any architectural design lies in its spatial organization. How will people move through the building? What spaces are essential, and how should their functions be arranged? This phase often involves the creation of massing models and floor plans, which evolve as feedback is integrated and the design is refined.

Aesthetic and Artistic Considerations

Even as function dictates form, the aesthetic quality of a building is paramount. Aesthetic decisions encompass everything from the building’s form and materials to the play of light and shadow within its spaces. Architects must consider the building’s relationship with its surroundings, aiming for harmony or contrast as appropriate.

Engineering the Dream: Structural and Mechanical Considerations

With the design taking shape, it’s time to ensure that the structure is not just beautiful but also sound. Engineers bring their expertise to bear, working alongside the architect to develop systems that will support the building’s function and form.

Structural Integrity and Safety

The structural system of a building is its skeleton, and it must be robust to withstand environmental forces and the test of time. A detailed structural analysis ensures that the design is both achievable and safe. This might involve assessing load paths, materials’ strength, and potential stress points within the design.

Mechanical, Electrical, and Plumbing (MEP) Integration

Modern buildings are intricate ecosystems of mechanical, electrical, and plumbing components. The MEP systems must seamlessly integrate into the architectural design, offering comfort, efficiency, and performance without compromising spatial and aesthetic goals.

Sustainability and Green Building Practices

Sustainability is no longer an afterthought in architecture—it’s a core principle. Engineers work to optimize the building’s energy performance, analyzing shading strategies, natural ventilation possibilities, and the integration of renewable energy systems. Water management and waste reduction also play significant roles in the engineering phase of a green building.

Navigating Regulations and Requirements: The Red Tape

No architectural project exists in a vacuum. Local regulations and building codes shape what is permissible and practical. Navigating this red tape is a necessary and often daunting part of the architectural process.

Understanding Zoning and Land Use Regulations

Zoning laws dictate how land can be used and what can be built on it. Architects and their teams must have a deep understanding of local zoning regulations to ensure that designs comply. This might involve negotiating variances or designing buildings that can be approved by right within zoning guidelines.

Building Codes and Safety Standards

Building codes are in place to protect the health, safety, and welfare of building occupants. Compliance is non-negotiable, and architects must be well-versed in the codes that pertain to their projects. This knowledge informs every aspect of the design, from egress routes to fire-resistant materials.

Cultural and Heritage Preservation

In some cases, architects must also consider cultural and heritage preservation laws. For buildings in historic districts or near significant landmarks, the design process might include maintaining certain aesthetic or structural elements to honor the site’s history while creating something new and vital.

Turning Ideas Into Tangible Entities: Construction and Execution

The construction phase is the transition from the abstract to the tangible. Architects often partner with construction managers to oversee the realization of their designs, keeping an eye on quality, timeline, and budget.

Contractor and Subcontractor Coordination

The architect serves as the client’s representative, coordinating with contractors and subcontractors to ensure that the builders understand the design intent. Regular site visits and design clarifications become the norm as the project comes to life.

Material Selection and Sourcing

Materials are the physical manifestation of design. Architects who choose materials carefully—balancing aesthetics, performance, and availability—contribute to a project’s success. Sustainable sourcing and the use of local materials can also reduce a project’s environmental impact.

Photography and Documentation

While construction can be a chaotic process, it’s essential to document the project’s evolution. Photography and written records capture the stages of development, providing valuable content for marketing, portfolio-building, and historical archive purposes.

The Finished Work: Post-Construction Evaluation and Fine-Tuning

Once the building is complete, the work is not necessarily over. Post-construction evaluation and occupancy studies inform future designs and fine-tune the current project for optimal performance.

Occupancy Studies and User Feedback

Occupancy studies observe how people use the space and whether the design supports its intended function. User feedback is invaluable, as it provides real-world data on comfort, usability, and any unexpected issues that might have arisen.

Fine-Tuning for Long-Term Success

Architects use the insights from occupancy studies to make any necessary adjustments. These might be small tweaks to the environment’s quality or more significant rectifications to address overlooked design flaws. The aim is to turn a building into a living, breathing entity that supports and enriches the lives of those it shelters.

Continuous Learning and Innovation: The Architect’s Path Never Ends

Each architectural project is a unique learning opportunity, a chance to refine skills, test new ideas, and contribute to the ever-evolving urban fabric. The process from concept to reality is never straightforward; it’s fraught with challenges and opportunities for growth. Yet, it’s in grappling with these complexities that architects push the boundaries of what’s possible, one building at a time. With every completed project, the architect’s vision expands—ready to conceive the next grand design.